Embarking on the Journey

Having reached a significant milestone in life, I’m finally setting out on a long-cherished journey to Dunhuang—a place I’ve always dreamed of visiting at least once in my lifetime.

As I mentioned in my article on the Chinese poem “Grapevine Wine,” I’ve had a deep fascination with the Western Regions since my youth. In middle school, I even declared, “Someday, I want to perish in the Taklamakan Desert.”

To fulfill this dream, I’m heading to China. I’ll document this journey in two parts on my blog: the “Preparation Phase” and the “Reflection Phase.”

- 1. Acquiring the “Globe-Trotter Travel Guide

- 2. Mastering Chinese Phrases

- 3. Rewatching the Film “Dunhuang”

- 4. Revisiting “Hiromichi Sekiguchi’s Grand Chinese Railway Journey: The Longest One-Way Route of 36,000 km”

- 5. Copying Chu Suiliang’s “Preface to the Sacred Teaching at the Wild Goose Pagoda”

- Preparing for the Western Regions’ Winds – Various Desert Travel Preparations

- Embarking on the Journey – After Completing All Preparations

1. Acquiring the “Globe-Trotter Travel Guide

I prefer having a physical travel guidebook at hand. For this trip, I sought out the “Globe-Trotter Travel Guide: Xi’an, Dunhuang, Ürümqi, the Silk Road, and Northwestern China.”

However, this proved more challenging than expected. Published in 2019, the guide is now out of print. Online searches yielded only used copies with varying conditions and prices. I ended up visiting multiple physical bookstores.

Eventually, I found a copy in a sweltering town while attending an exhibition by a respected calligraphy teacher. It felt like fate guiding me, and I couldn’t help but pump my fist in triumph upon finding it.

2. Mastering Chinese Phrases

Even with advanced translation software, it’s essential to learn basic local phrases. I used NHK’s “Gogakuru” as a reference.

Greetings:

- Thank you! 谢谢!(Xièxie!)

- Hello 你好!(Nǐ hǎo!)

- Excuse me. 不好意思。(Bù hǎoyìsi.)

- I’m sorry. 对不起。(Duìbuqǐ.)

- It’s okay. 没关系。(Méi guānxi.)

- You’re welcome. 不客气。(Bú kèqi.)

- I’m Kato. 我是加藤。(Wǒ shì Jiāténg.)

Responses:

- Yes. / No. 对。/ 不对。(Duì. / Bù duì.)

- There is. / There isn’t. 有。/ 没有。(Yǒu. / Méiyǒu.)

- Understood. 明白了。(Míng bái le.)

- Indeed! 可不是吗!(Kě bú shì ma!)

- Amazing! 真了不起!(Zhēn liǎo bu qǐ!)

- So-so. 还可以。(Hái kěyǐ.)

- Just looking. 我随便看看。(Wǒ suíbiàn kànkan.)

Questions:

- Excuse me, where is the restroom? 请问,洗手间在哪儿?(Qǐngwèn, xǐshǒujiān zài nǎr?)

- What is this? 这是什么?(Zhè shì shénme?)

- What should I do? 怎么办?(Zěnme bàn?)

- How do I get there? 怎么走?(Zěnme zǒu?)

- How do you write this? 怎么写?(Zěnme xiě?)

- What’s wrong? 怎么了?(Zěnme le?)

Requests:

- The bill, please. 买单。(Mǎidān.)

- One of this, please. 要一个这个。(Yào yí ge zhège.)

- Could you speak more slowly? 请慢点儿说,好吗?(Qǐng màn diǎnr shuō, hǎo ma?)

- Please wait a moment. 请等一下。(Qǐng děng yíxià.)

- Sorry, please wait another 10 minutes. 不好意思,再等十分钟。(Bù hǎoyìsi, zài děng shí fēnzhōng.)

- Let me think about it. 让我好好儿想想。(Ràng wǒ hǎohāor xiǎngxiang.)

3. Rewatching the Film “Dunhuang”

The film “Dunhuang,” released in 1988, is a Japanese-Chinese co-production directed by Junya Satō and starring Kōichi Satō. It’s based on Yasushi Inoue’s novel “Dunhuang.”

Set in the 11th century, after the Tang Dynasty and during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, the story follows Zhao Xingde, a young scholar caught in the turmoil of war in the Western Regions, particularly in Dunhuang—a key point on the Silk Road. The film poignantly portrays people’s deep reverence for culture.

For instance, there’s a scene where the Western Xia people proudly explain their unique script, derived from Chinese characters. Though no longer in use, their desire to record their language in their own script is deeply moving.

Later, Zhao hides Buddhist scriptures and murals deep within caves—a depiction based on historical events. In the late 19th century, a vast collection of documents known as the “Dunhuang Manuscripts” was discovered in the Mogao Caves. The film thoughtfully explores why these were hidden and preserved.

The passion of those who risked their lives to protect culture and faith is overwhelming. Thanks to their efforts, we can now witness the Dunhuang Manuscripts. The film’s stunning desert visuals and its quiet narrative about knowledge left a lasting impression. It reminded me that culture isn’t just passed down—it’s created and safeguarded by people’s hands, underscoring our responsibility in the present.

4. Revisiting “Hiromichi Sekiguchi’s Grand Chinese Railway Journey: The Longest One-Way Route of 36,000 km”

This travel program aired on NHK in 2007. Sekiguchi’s unpretentious personality, rich sensibility, interactions with locals, and diverse landscapes made it captivating—I recorded and rewatched it multiple times.

This time, I revisited the program and its accompanying book, filled with Sekiguchi’s insightful illustrations.

Notably, in the 43rd episode, Sekiguchi travels from Wuwei to Zhangye and then to Dunhuang in Gansu Province—a route I will also take.

While I may not have the opportunity to converse leisurely with locals as he did, the thought of seeing the arid landscapes, endless tracks, and bustling stations he experienced fills me with anticipation.

Sekiguchi’s reflections on China’s vastness and the warmth of its people offer valuable insights for my journey. Even within a limited timeframe, I hope to absorb and bring back something meaningful. With these thoughts, I concluded my “preparation” through the screen.

5. Copying Chu Suiliang’s “Preface to the Sacred Teaching at the Wild Goose Pagoda”

Chu Suiliang was a politician and calligrapher during the early Tang Dynasty. I plan to visit the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, home to his renowned stele, the “Preface to the Sacred Teaching.”

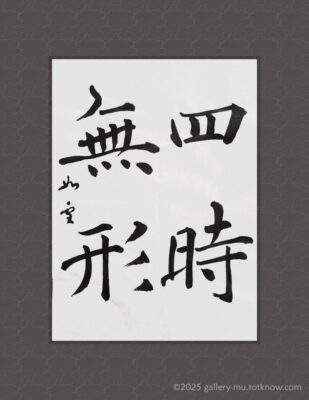

| Title: | 四時無形 |

|---|---|

| Size: | about 33×24 cm |

| Dressing: | framed |

Coincidentally, a high school student I’m teaching is currently working on this piece. Revisiting it through copying, I found myself captivated by its charm.

Chu’s calligraphy isn’t just beautiful; it exudes strength and elegance. There’s softness within discipline and dynamism within tranquility. It’s meticulously detailed yet warm—a true ideal in calligraphy.

Each stroke feels like touching the air of the Tang era. Tracing this work by hand before visiting Xi’an (formerly Chang’an) feels like a luxurious preparation.

Copying isn’t just about acquiring knowledge; it’s a gateway to experiencing the journey physically. It provided a serene and enriching time to mentally prepare for the Western Regions.

Preparing for the Western Regions’ Winds – Various Desert Travel Preparations

Travel Preparation 1: Food Considerations

I have a mild wheat allergy. Since this is a tour, meals may include noodles. While alternative menus are available, I prepared my own food just in case.

A thoughtful friend sent me a soup set, alleviating concerns about vegetable intake.

Other items I packed:

- Egg porridge – a convenient protein source

- SOYJOY – a wheat-free nutritional bar

- Freeze-dried miso soup – a comforting taste of Japan

Travel Preparation 2: Adding a Chin Strap to My Hat

In the sun-drenched desert, a hat is essential. However, strong winds could blow it away, so I customized it with a chin strap.

I sewed tape onto the hat to attach the clip, sealing the tape ends with a lighter to prevent fraying. I ensured the strap would sit just in front of my ears.

The chin strap, equipped with a UV-sensitive adjuster, was a handy find at Daiso. It’s surprisingly effective, even indicating UV intensity.

Now, even when cycling, I can rest assured my hat will stay put.

Embarking on the Journey – After Completing All Preparations

Having acquired the “Globe-Trotter Travel Guide,” practiced Chinese phrases, rewatched the film “Dunhuang,” revisited Sekiguchi’s railway journey, and copied Chu Suiliang’s calligraphy, I’ve completed my preparations.

From the food I packed to the modifications on my hat and the new raincoat, every detail has been considered.

Now, it’s time to set off on this long-awaited journey to Dunhuang. I look forward to sharing my experiences in the upcoming “Reflection Phase” of this blog series.

再見!